“About time, too. He’s been looking dreadful for days; I’ve been telling him to get a move on.“—Albus Dumbledore about his phoenix Fawkes after Fawkes burst into flame

Just as Fawkes periodically must burst into flames and rise again from the ashes, so must my longstanding website project, BirdWalker.com. To better understand why it’s time for me to “get a move on”, here’s some background.

A brief history of BirdWalker

I’ve been watching birds since the mid-1990’s and programming computers since the early 1980’s. When my wife Mary and I started birding, I kept notes on paper while out watching birds. I wanted to count how many different bird species I’d seen in a given month or year or county. I quickly realized I wanted a database to help me track these numbers, and thought it would be fun to build one from scratch. When I started photographing birds a few years later, I wanted to count how many different bird species I had photographed as well. BirdWalker 3 is the the third incarnation of that tool. Here’s a quick look at how BirdWalker evolved.

Version 1, FileMaker Pro

I got serious about birding during the height of my FileMaker Pro obsession. FileMaker Pro was a simple database engine combined with user interface tools. I made my first birding database with FileMaker Pro. I ran it locally on my own laptop and never hooked it up to the web. I used my Palm V to record sightings in the field. Although there were ways to publish FileMaker Pro databases as web sites, I never got around to using them.

Version 1.5, XSLT

In 2001, while working at Reactivity, I had the idea to export my FileMaker Pro data as XML text files while I was learning XSLT. XSLT (eXtensible Stylesheet Language Transformations) is a language for describing how to transform one file format into another. I transformed the raw data of my bird sightings into a website of different kinds of reports, all linked together. I became the XSLT expert at Reactivity (there wasn’t much competition for that title, believe me). I disliked SQL databases and hadn’t really learned about CSS or JavaScript, so I was using XSLT to do the work of a database and an application server and a presentation layer. The complexity of the resulting code, plus XSLT’s arcane syntax, lead to an idiosyncratic, unmaintainable monster.

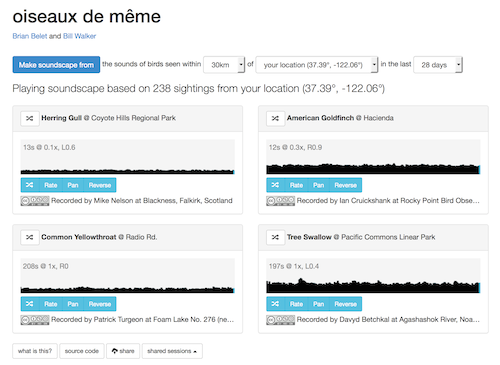

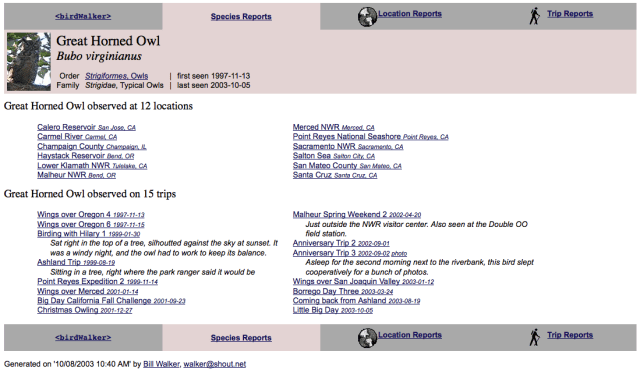

BirdWalker, XSLT version, October 2003. This page is a species report showing all my observations related to Great Horned Owls, including when and where I observed them, plus my first photo of this species

Version 2, Linux, PHP, MySQL

In 2003, I decided to abandon XSLT, overcome my distaste for SQL databases, and begin again in PHP and MySQL. This combination of tools, also known as LAMP, was much easier to learn and manipulate than XSLT, so I was able to build things much more quickly and easily. In addition to producing summaries and reports of my birding notes, I added the ability to record new notes right into the website.

In hindsight, my biggest mistake during this PHP era was ignoring the PHP community and their wisdom about how to cope with software complexity. Lacking role models, I ended up with a codebase that mingled topics that should have been kept separate, what Brian Foote calls a Big Ball of Mud. My code didn’t cope with errors, wasn’t well tested, and couldn’t be easily extended.

Version 3, Ruby on Rails

In 2007, I saw the classic Ruby on Rails “make a blog in 15mins” video and was hooked. I created the BirdWalker 3 repository on GitHub and started on a new version using basically the same SQL schema as I used with PHP. Thanks to the Rails scaffolding generator and separation of concerns, I ended up with structured code and automated tests. I also adopted Twitter’s Bootstrap framework, so the web site would work on both my iPhone while out in the field and on my laptop back home. BirdWalker version 3 is still the code that runs when you visit birdwalker.com.

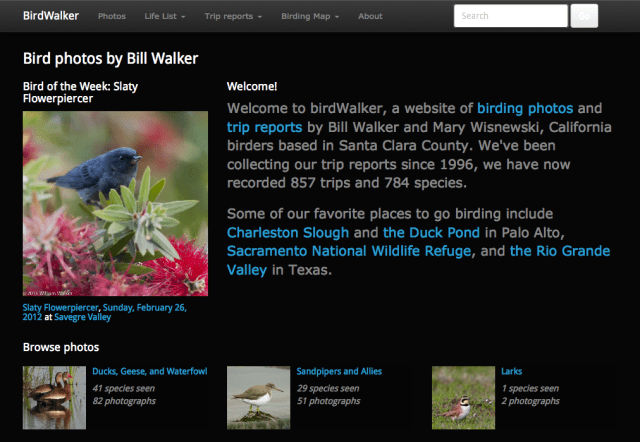

BirdWalker, Ruby on Rails version, February 2016. The homepage consists of several Rails partial templates that can be rearranged as needed.

I like it well enough, but there are some big problems:

Big ball of mud

I’ve mostly forgotten how my own Rails code works — my Rails HTML templates and CSS styles are overly complex and hard to modify. Also, there are a lot of half-finished parts, such as better ways to do editing and heuristics for adapting page templates to varying amounts of data.

Application server — slow and overpriced; necessary?

I’m hosting BirdWalker 3 on an Amazon EC2 m1.small instance running MySQL and Rails. This both costs more than I want while being slower than I’d like. Given that the data in the SQL database only changes when I add new sightings (once or twice a week), administering and paying for this whole server feels like overkill.

The ascendance of eBird

While I was building and living with BirdWalker 3, Cornell University’s eBird grew and gained prominence among the birders I know. I exported my SQL database into the eBird format, and uploaded over 20,000 sightings into my eBird account. This is my contribution to eBird’s massive citizen science project, which I love. eBird also lets me compete with my peers in logging the most eBird sightings.

But now I have two sources of truth for my birding life, BirdWalker and eBird. As eBird matures, I find that maintaining my own data entry tools for birding makes no sense. I’d much rather do all my data entry at eBird and then base my website on data exports from eBird.

Arising from the Ashes

I’ve made two experiments since 2013 in preparation for replacing BirdWalker 3. The first was about replacing Ruby on Rails with JavaScript and Angular. The second was about replacing server-side code with static hosting.

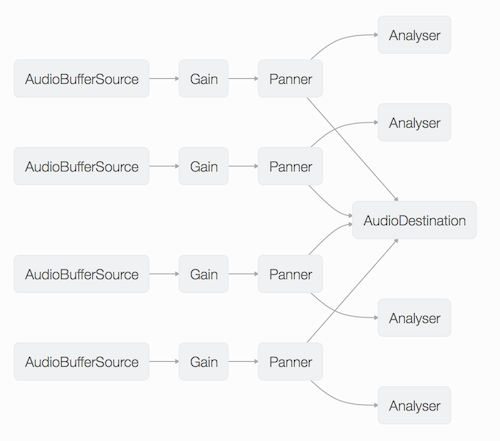

An Angular transplant

I have frequently and loudly evangelized the advantages of single page web apps as part of my work at Mozilla. Following my own advice, in August 2013 I started to rework BirdWalker using Angular. (I actually tried twice, once with a web components library named Brick and a second time with Twitter Bootstrap). I recreated almost all of the reporting and browsing parts of my site using Angular controllers and templates (see http://birdwalker.com/angular/#/home). My Rails server-side code was reduced to a modest JSON API. Unfortunately, that code was still limited by SQL performance.

Static hosting of data-driven sites

In 2015 I was inspired by talks at the first GitHub Universe conference and a publishing tool my Mozilla coworkers made called Oghliner. This led me to experiment with publishing this site on GitHub Pages, moving all the application logic into the browser. I created a new code repository called ebird-mybird. I wanted to discover whether I could build a client-side web experience for browsing the CSV text file export from eBird. I’ve used these building blocks:

- Handlebars for client-side templates

- Oghliner for offline access using Service Worker

- PapaParse for parsing CSV

- Mocha for unit tests

- Gulp for build tasks

- Lunr for full-text search

The results so far are functional, if not yet beautiful. It lets me view bird lists for individual days, whole years, specific locations, counties, and states. I’ve got a search that lets me find individual species and locations and trip names. When I make changes to the software, Oghliner automatically rewrites my service worker and updates GitHub Pages using Travis-CI. On most laptops with broadband, the front page starts drawing in less than half a second, and the whole site is ready in about 3 seconds. On my iPhone 5, the front page starts drawing in less than a second, but takes 25 seconds to load completely, way too slow. Almost all of that time is spent parsing 4MB of eBird data, which is crazy. Almost as crazy as writing a website entirely in XSLT.

Now what?

Having discussed the above with several folks, I think my next step is to parse the CSV file on the server instead of the client, and to make a simple NodeJS server with a simple REST API that talks to a client with either the Handlebars templates I built or the Angular code I abandoned. I’ll keep you posted.